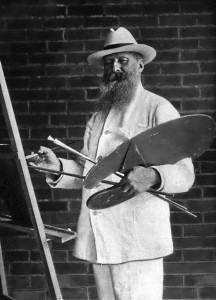

Vasily Vereshchagin fæddist árið 1842 í Rússlandi. Á unglingsárunum lærði hann til sjóliða í Sankti-Pétursborg og sigldi á gufuskipinu Kamchatka til Danmerkur, Frakklands og Egyptalands. Hann fór seinna í háskólann í Sankti-Pétursborg og 22 ára fór hann til Parísar þar sem hann lærði málaralist undir Frakkanum Jean-Léon Gérôme sem lagði mikla áherslu á menningu Austurlanda.

Á seinni hluta 19. aldar ferðaðist Vereshchagin víða, meðal annars til Túrkestans (í dag Úsbekistan), Sýrlands, Palestínu, Indlands, Filippsseyja, Kína, Japans, Bandaríkjanna, Kúbu og Tíbet og sýndi verk sín í München, Berlín, Dresden, Vín og London. Hróður hans fór víða. Hann var vitni að stríðsátökum í Túrkestan (Úsbekistan), stríði Rússa og Tyrkja 1878-1879, Japana og Kínverja 1894-5, Boxarauppreisninni í Kína 1900. Hann lést um borð í herskipinu Petropavlovsk sem sigldi á tundurdufl við Port Arthur í stríði Rússa og Kínverja 1904-5.

Málverk hans voru bönnuð af rússneskum yfirvöldum vegna þess að þeim þótti hann draga upp slæma mynd af rússneska hernum og hernaði almennt. Sagt er að þýski hershöfðingjnn Helmuth von Moltke hafi skoðað sýningu á verkum Vereshchagins árið 1882 og lagt blátt bann við að þýskir hermenn skoðuðu sýninguna (stríðsmálaráðherra Austurrísk-Ungverska keisaradæmisins á að hafa gert það sama). Eftirfarandi textabút skrifaði Vereshchagin sem inngang að málverkasýningu sem haldin var í Pennsylvaníu í Bandaríkjunum árið 1889:

Observing life through all my various travels, I have been particularly struck by the fact that even in our time people kill one another everywhere under all possible pretexts, and by every possible means. Wholesale murder is still called war, while killing individuals is called execution. Everywhere the same worship of brute strength, the same inconsistency; on the one hand men slaying their fellows by the million for an idea often impracticable, are elevated to a high pedestal of public admiration: on the other, men who kill individuals for the sake of a crust of bread, are mercilessly and promptly exterminated—and this even in Christian countries, in the name of Him whose teaching was founded on peace and love. These facts, observed on many occasions, made a strong impression on my mind, and after having carefully thought the matter over, I painted several pictures of wars and executions. These subjects I have treated in a fashion far from sentimental, for having myself killed many a poor fellow-creature in different wars, I have not the right to be sentimental. But the sight of heaps of human beings slaughtered, shot, beheaded, hanged under my eyes in all that region extending from the frontier of China to Bulgaria, has not failed to impress itself vividly on the imaginative side of my art. And although the wars of the present time have changed their former character of God’s judgments upon man, nevertheless, by the enormous energy and excitement they create, by the great mental and material exertion they call forth, they are a phenomenon interesting to all students of human civilization. My intention was to examine war in its different aspects, and transmit these faithfully. Facts laid upon canvas without embellishment must speak eloquently for themselves.

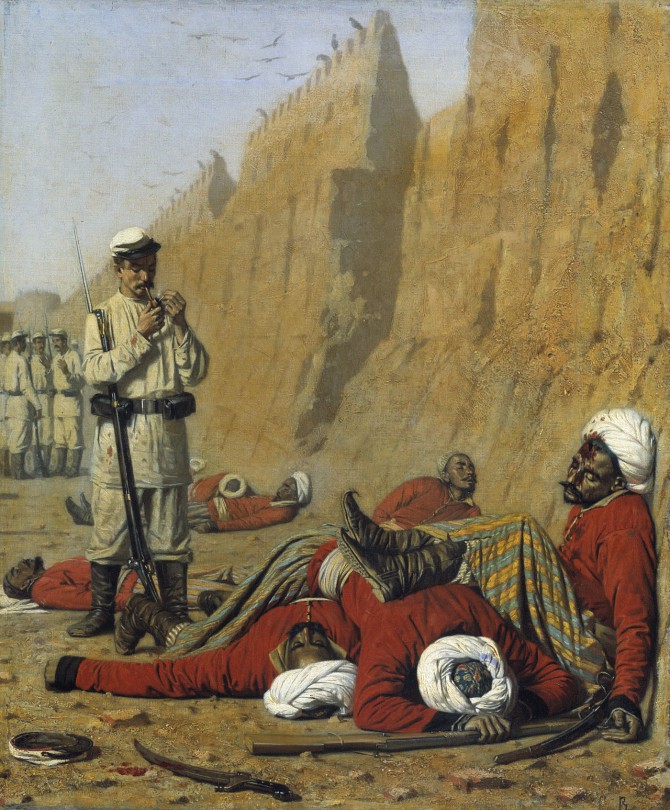

Málverkið „Við kastalavegginn: Veitið þeim inngöngu!” frá árinu 1871 sýnir Rússa hertaka kastalann við Khiva, sem tilheyrir Úsbekistan í dag.

Málverkið Hápunktur stríðsmennsku 1871 átti upphaflega að vera tileinkað Túrkmenanum Tímur (1336-1405), stofnanda Tímúrveldisins en Vereshchagin ákvað að tileinka verkinu „öllum stórkostlegum herforingjum, í fortíð, samtíð og framtíð.”

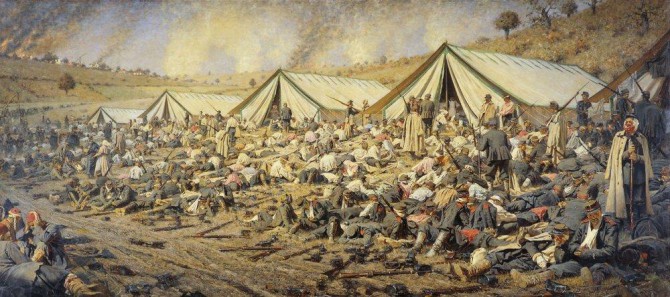

Málverkið „Eftir árásina: sjúkrabúðirnar við Plevna” frá 1881 sýnir aðstæður í orrustunni við Plevna í stríði Rússa og Ottóman-Tyrkja 1877-8.

Málverkið „Skotið úr byssunum” í Indlandi Breta frá árinu 1884 sýnir mjög ógeðfellda aftökuaðferð þar sem fórnarlambið er bundið við fallbyssu sem svo er hleypt af. Myndin er ekki sögulega nákvæm en sagt er að Bretar hafi keypt myndina og látið eyðileggja.